Challenges

/I have to remind myself throughout history, people have lived with a sense of crisis. Flick through an account of the world and one thing becomes evident: conflict and disease have set the tone of most eras. The 30 Years War, the 100 Years War, the World Wars and Cold War, Black Deaths and Blue Deaths, bad things come in every length, temperature and colour. So, I should bear that in mind when trying to make sense of the heaviness that has grown since the pandemic. Crisis has been the world’s watchword, I just hadn’t lived long enough to recognise the pattern.

There is some comfort in knowing that this is probably the standard way of things and the relative idyll of my former years, was either the result of a protective, ignorant bubble or a momentary respite from the status quo. Difficulties are not a worrying new phenomenon, rather they are a fundamental component of life, adding context to the question of human existence - what are we to do with our time?

Life is a challenge. Watching my child develop has been a demonstration of this. Within the space of 18 months a mewling, downy creature has learnt to roll, sit, crawl and stand. His limbs have grown long and teeth have erupted through his gums, causing much misery and much joy. What at first appeared to be a hairless guinea pig has transformed into a little boy who can run, sing and chomp on apples and crackers with gusto. But each step was hard-earnt, the result of countless hours of practice and trying.

And for what? Has he learnt it all yet? Is he done? Not by any stretch of the imagination. There is so much more to come. Yes, he can run, but can he skip yet? Can he hop? Can he do the long jump and the foxtrot and the macarena? No, that’ll all have to be learnt. And then there is language - so many words that need to be coded into his brain! He needs to learn how to form a sentence and form a rhyme and the most precious challenge of all, learn to read.

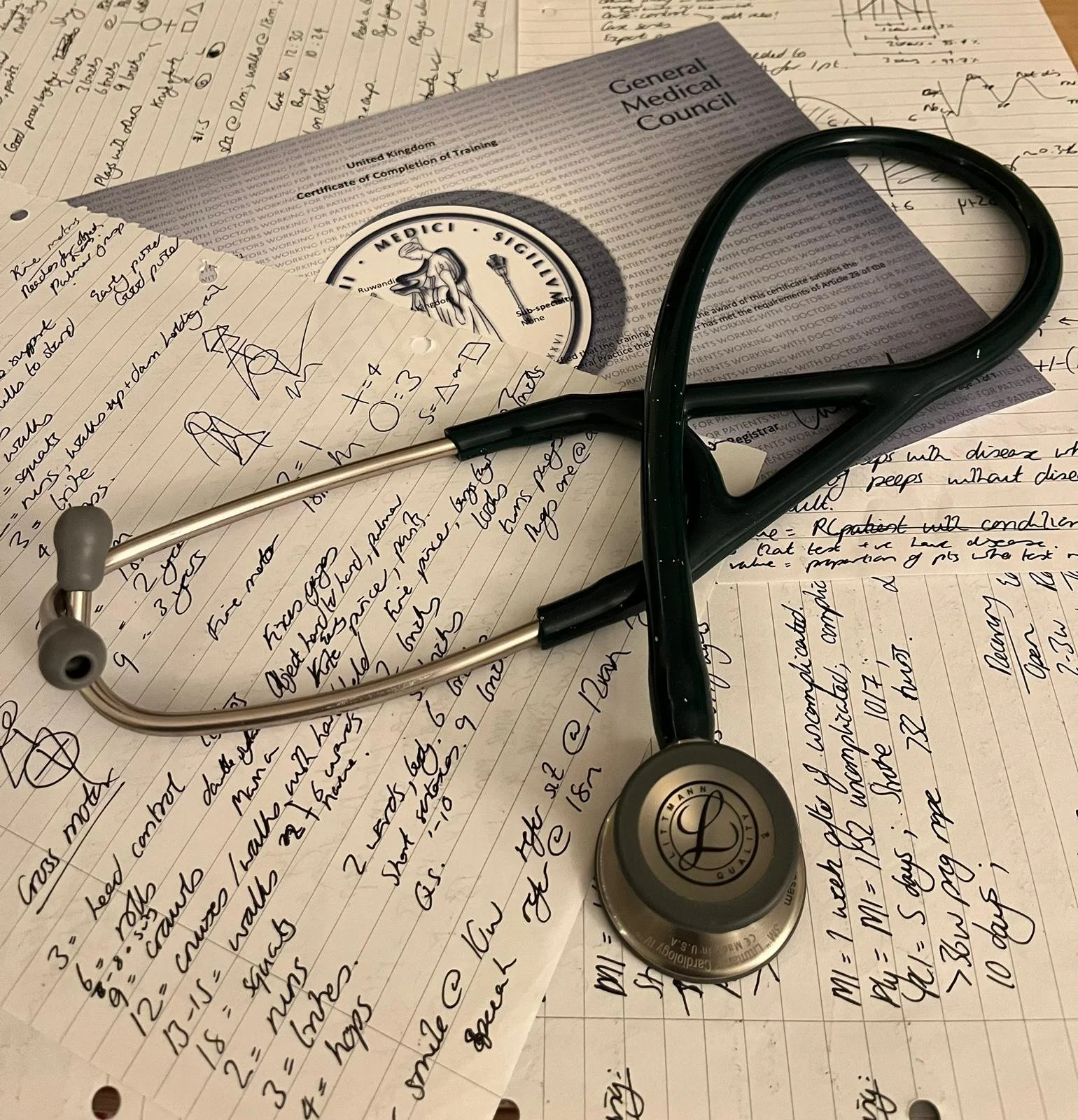

The difficulty is not done with. It will be a lifelong process, something I have had to remind myself of, as I sit down to reflect on my own year of surprising challenge. I thought by now I’d have it all figured out and I’d finally be settled in all aspects of my life. Maybe it was naive to think that by the age of 36 there would be no more obstacles to overcome and I would instead cruise out the rest of my days, doing the same job in the same location. But circumstances in and out of my control have made a mockery of that thought. Even if I were able to control most of the factors in my own life, I have no control over other people’s fates or the greater changes in the world at large.

I have had to learn this lesson over the past year and it has been a startling epiphany. Things may not go my way, loved ones might die and I might (actually probably will) live in difficult times. This realisation has had the effect of being cast out of Eden, but now am beginning to see the way past disillusionment. I have found consolation in many different places, not least literature.

“I wish it need not have happened in my time,” said Frodo.

“So do I,” said Gandalf, “and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

Lord of the Rings, J. R. R Tolkien

In the end, all we have is our time. I am grateful for the gift of another year, for more opportunity to decide what to do and how to overcome the obstacles set before me. I am not done with challenge yet, I suspect I won’t be for some time to come.